As anyone who's had to study this topic will tell you, the problem with a single European monetary policy, is that when the Euro area experiences an economic shock different countries will react differently. The example generally given, is to compare the effects of a shock to Greece's aggregate demand that fails to materialise in Germany's. Several scenarios can be contemplated. The shock could have been to export demand, to savings, investments, or public spending, which is so severe that it forces the Central bank to intervene. The latter scenario is appealing, because it is pretty much what's happening at the moment in Greece.

As the interest rate decreases in the Eurozone, coetris paribus, so does the exchange rate. The mechanism can be thought of in at least two ways. The first case is the carry trade scenario, where investors borrow cheaply in €, then convert them to US$ (or whatever, probably Chinese Renmimbi) in order to reap higher returns. This conversion would dump € into the FOREX market, causing the currency to depreciate. Secondly, the carry trade hypothesis may be exagerated. In that case it is possible that a decrease in the interest rate demanded by the central bank decreased the interest rate offered on returns to investments in the private sector. Thus by making € denominated investments less interesting, market actors decide to move their shed their assets bearing interests in € and replace them by more profitable assets in another currency.

The second case however, is the one closest to scenario facing Greece. The shock in and of itself was so strong that it caused investors to leave Greece, because it seemed unable to provide credible or acceptable levels of returns to any form of investment, due to economic stagnation. Interestingly, if the Greek stress on the currency union does not threaten the viability of businesses in other € countries, then instead of facing risky FOREX markets the investors in the Greek market, will simply transfer their € investments from Greece to Germany. This would leave the nominal exchange rate more or less unchanged. However, lets work with the scenario closest to the current situation, where initially, the shock in Greece, caused a devaluation of the €.

The consequence here is what matters most, not so much how we get there. And the consequence is that if they did not share a common monetary policy, Germany's real exchange (interest) rates could stay still, while its Greek counterpart would be lowered to adapt and deal with the new situation. However, as the figure (page 355, of Baldwin and Wyplosz)below shows, once both economies share a common central bank, Greece’s interest rate adjustment also applies to Germany.

Given that it is completely inappropriate to that country, the result will be a milder reaction from the central bank. Instead of adjusting completely to the shock in Greece (point B), real rates will only decrease by a fraction of what they would otherwise (to point C), in order to take Germany’s economy into account, and not overheat it too much. As a result, aggregate supply in Greece is higher than demand(C'-C), while at the same level of real exchange (interest) rates aggregate demand in Germany is higher than supply (D'-D). As this desiquilibrium cannot last some further adjustment will have to occur at the level of wages and prices. Contrarily to the very simplified view offered by Baldwin and Wyplosz, I believe that the realm of possible results is much larger than a simple wage decrease for Greece and a price increase for Germany. Many things may be at play in both countries, and the actual adjustment will reflect national labour market arrangements.

The variables of relevance are wage and price mark ups, productivity, and the level of unemployment. In all cases however, the result will most certainly be a deflationary contraction of Greece’s GDP, through a negative shock in the aggregate supply. Germany, however, may or may not face an inflationary pressure. Where as Greece must pay less to it's workers and most likely will also have to fire them, thus increasing unemployment, German firms may be able to boost productivity, increase wages and prices or simply hire more workers at the same wage producing products sold at the same price. Thus, whereas we know that the situation will cause deflation in Greece, the German labour market may or may not use this opportunity as an excuse to raise inflation.

Boosting productivity is difficult and unpredictable, because it basically requires a change in either management techniques or a technological advancement. Increase the price of products, thus selling the same amount of product at a higher price is another alternative. This would lead to an increase in the wages of workers, in the bonuses of managers and or in the dividends of stockholders. In my view, this is a bit un-German, as it seems to me that they are rather export savy. Nonetheless this is the scenario contemplated by Baldwin and Wyplosz. Those authors argue that this situation would be equivalent to a shift along the supply curve from a momentary desiquilibrium from (D-D') and push it up back to the initial point A. This is because the adjustment in the real exchange rate would occur at the level of inflation, not at the level of the nominal exchange rate. As those authors explain under these circumstances EMU will result in “recession and disinflation for Greece and boom and inflation for Germany (…) when an asymmetric shock occurs”.

The third alternative (which I find more realistic) is that German firms expand their market share and produce more, rather than charging more for the same quantity. In order to do that, they'll have to hire people thus decreasing the unemployment rate and increasing output, in a positive supply shock. Through this process prices will remain constant and German firms will be able to take advantage of the new nominal exchange (interest) rate and become more competitive, which will be seen by a lower real exchange rate than at the beginning.

Thus, in the scenario that I am contemplating will lead to Greece having higher inflation and lower GDP than outside of the EMU, while it will lead Germany to have lower inflation and higher GDP, than if it were outside.

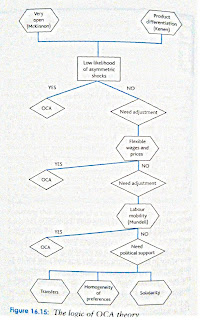

In all these cases, the important thing is to understand how the real exchange rate reacts to the change in the nominal exchange rate and what can be done to mitigate the ensuing economic heterogeneity within the EMU. Remember that homogeneity is desirable because it means that a single monetary policy is applicable to the whole currency area. It is to these homogenising factors, as decribed by the figure below (page 370, of Baldwin and Wyplosz), that I now turn my attention.

Price and wage rigidities

First, if prices and wages are flexible then adjustment will occur faster than if this is not the case. If Greek supply is superior to demand, retailers won't be able to sell products and eventually they'll communicate this to producers who will then decide to produce less. As a result they'll have to decrease their production volume. Assuming that the quantity of output produced is a function of labour input, then labour will have to be fired, causing unemployment to increase, while as less people work, labour may become more expensive, pushing wages up, as well a prices. This causes the AS curve to contract seen as a decrease in the price level leading to the adjustment in the real exchange rate of Greece.

At the same time in Germany, the extra demand will tend to cause a response to the market from the supply side, which will hire more people to produce more of the output. If wages are very responsive then we’ll be contemplating scenario number two, favoured by Baldwin and Wyplosz. Alternatively, it may be that the German labour market is more conservative, and inflation averse, with a bigger preference for lower employment than for high wages. Thus wages remain the same and as described in my favoured scenario number 3, output increases for the same level of real exchange rates. This is actually a very good point, given that it describes an actual fact, that the German labour Market is less greedy than the Greek (or than the Portuguese, Spanish or Greek for that sake). There might be a good reason for this as Germany is more dependent on trade than Greece. Thus, job stability is more directly linked to international competitiveness and as such is much more fragile than in those countries where supply is more geared to domestic consumption where firms are exposed to political pressure from a government lobbied by trade unions that do not internalize competitive pressures (because none exist). Thus wage flexibility might also be a function of exposure to trade pressures.

Labour Mobility

Labour mobility enters the debate in the context of the feasibility of supply in Germany being able to meet its international demand. It is possible that German firms may be unable to hire more workers, because the economy is at full employment or because there are no more qualified workers available to do the job. In that case the demand/supply desiquilibrium would persist. A solution may be to import Greek workers. This would speed up the adjustment process. However, we don't have a unified labour force as the USA have. This isn't completely caused by barriers created by countries. Most likely it is a result of the fact that we speak different languages, which complicates mobility from one country to another. Obviously more could be done, in the sense that states could improve the portability of state and corporate pension funds in order to decrease the costs of labour mobility, but that's also a problem in the USA (even if only to a smaller proportion). More to the point, without labour mobility wages take a little bit more time to adjust to asymmetric shocks.

Fiscal transfers

But none of this explains why fiscal federalism at the EU level is an obviously desirable development. The situation as it is implies that EMU between heterogeneous economies creates winners and losers. This is clearly true, as it tightens the belt of the less efficient and stimulates the more efficient. In order to deal with this, the OCA theory proposes voluntary fiscal transfers between member states. It argues however that in order for these to be feasible, it is necessary for there to be solidarity and homogeneity of preferences. The idea is that in the absence of price and wage flexibility, and of labour mobility, intergovernmental transfers, because they are voluntary require some form of incentive. Here the authors focus the stimuli of altruism (solidarity) and self interest (implied by sharing common interests. My impression is that the main reason driving member states to accept to provide transfers for one another is that their economic links to each other are so high and they are all so exposed to spillovers from one another that the damage experienced by one is experienced by a considerable number of others.

However, as the next posts mention intergovernmental arrangements do not work, due to a number of collective action problems and of dynamic inconsistency. Delegation of this redistributive fiscal policy to the European Commission would be equivalent, and as the fourth part shall argue it would not suffer from all of the problems that would plague voluntary intergovernmental transfers. It would tax Germany's income to subsidise Greek unemployment and retraining. Not for nothing, but given that in this context German excess growth has only happened due to Greek pressure for lower exchange (interest) rates, it seems fair to me to tax them. Of course the taxation would only be so high as to cover the GDP loss that Greece would have experienced had it been able to set the interest rate at its ideal post shock level. The risk of course is the mezziogiornalisation of the euro-area.

This is the "irrefutable logic" of introducing one or more forms of EU taxation. The obvious problem nonetheless, is that not withstanding the irrefutability of the logic for a EU tax, there are practical concerns to take into account. National Governments' concerns of eroding sovereignty is the first concern. Popular support is the second one and the one which the FT Lex article touches upon, but these seem to me as overly advanced secondary concerns. Before any negotiation on a policy of this scope, I believe that the EU needs to be on the same level as its composing member states. Thus the EU needs to enjoy some legitimacy. That takes me to the next post.

No comments:

Post a Comment